My West Indian Grandparents’ Legacy

I share the remarkable story of my West Indian grandparents from Barbados and Trinidad. Their resilience, cultural heritage, and enduring legacy in Brooklyn have shaped who I am today. Discover their inspiring journey of love, strength, and family.

I was beginning to write about my grandfather until I realized I couldn’t tell his story without telling my grandmother’s. For much of my life, I saw them not as a couple but as separate entities. But their stories are intertwined, complex, and any other description would fall short because they were both perfect and flawed—in other words, they lived incredibly human lives. And I am both their legacies.

My grandmother, whom we call Nandi, once asked me, “What do you want to be when you grow up?”

“Well, Nandi, I think I want to be a doctor,” I replied.

Her response was blunt: “You’ll never be a doctor.” She left it at that; I was six. At the time, her words stung. But looking back, I realize she valued preparedness and perhaps wanted me to understand that the path wouldn’t be easy.

Nandi has many more famous moments. Once, my two brothers were playing in the car and not paying attention. She assumed my younger brother was misbehaving and yelled, “Landon, if you don’t stop, I will pull out all your eyelashes.” When my mother was seven and said she wanted to be a writer, my grandmother replied, “What do you want to be that for? You’ll make no money, and people don’t care about writers until they’re dead.” Nandi’s bluntness was her way of expressing concern, maybe shielding us from disappointment by lowering our expectations.

While she may come off as rash, she actually just values authenticity—perhaps in excess. She believes in facing the world head-on, without illusions. But as she’s aged—now 95 years old—her heart has softened, and I’ve come to understand the layers beneath her tough exterior.

I spoke to her today about her past. She told me bluntly that she was the talk of the town. Many men were interested in her and assumed she would be back, but she often told them, “Go to hell”—another one of her famous phrases. My grandmother does not and never has played around.

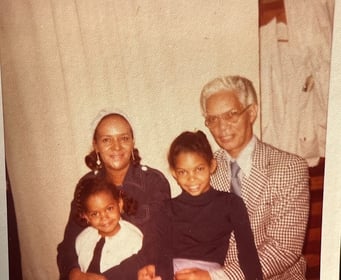

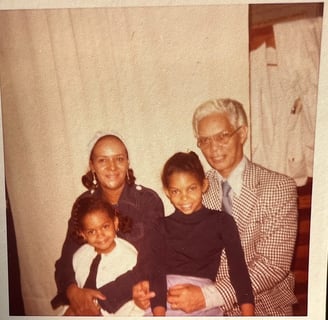

She didn’t care for most of the men who crossed her path, but she did end up marrying my grandfather. Apparently, she knew him long before they even dated. Growing up in Brooklyn, everyone knew each other, including the tall, fair-skinned Trinidadian man who was Benthen—or Grandpappy to me. Nandi’s family was West Indian too, from Barbados, so they shared a cultural connection that went beyond the streets of Brooklyn.

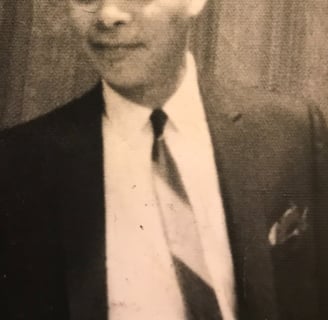

Allegedly, every girl in Brooklyn wanted to know my grandfather. He immigrated from Trinidad as a child and lived with his four siblings in a brownstone on Putnam Avenue. He joined the army during World War II, serving overseas. The war undoubtedly left its marks on him, though he rarely spoke of it. Upon returning, he went to law school and became a lawyer—the only professional in his family. Eventually, he ran for judge in Brooklyn, an immense feat for a young Black man in the mid-20th century. He had a certain soft charisma that was awfully alluring when combined with his fair skin, wavy hair, and always-pressed suit and tie. At the Chinese restaurant, the workers would bow to him when he entered out of respect. Grandpappy was definitely the talk of the town.

I asked Nandi what she was looking for in a man when she met my grandfather.

She said, “Well, I wasn’t looking for him.”

I anxiously laughed and asked for clarification because it didn’t make sense to me.

“You can’t know who you want; you never know who you’re going to click with,” she explained.

That line stuck with me.

When my grandparents married, my grandmother would walk down the street like she was royalty. For all she knew, she had married the fair-skinned, gray wavy-haired president. When Grandpappy had my mother and her sister, he loved to read and encouraged habits that stick with them to this day. He would take them to the park, point at trees, and recite poetry. He took them to fancy restaurants to show them that they deserved such experiences. He used to say, “A man should take you to a place that matches this caliber or exceeds it.”

He was also a creative soul. I mentioned his love for poetry, but he could sing a bit too. He was an amazing visual artist and spent time crafting countless beautiful paintings. Grandpappy was more than knowledgeable and diligent; he was wise. He embodied the qualities of a Renaissance man—educated, artistic, charismatic.

But his good heart and wisdom couldn’t shield him from inner turmoil. The experiences from the war

lingered, haunting him in ways that weren’t openly discussed back then. Losing the election for judge was a catalyst that worsened his struggles. Soon after, Grandpappy started spending less time with books and more time on the couch. His spirit was low, and it wasn’t long before he was diagnosed with clinical depression and began carrying around a large brown paper bag of medicine. The man who once commanded respect wherever he went was now walking across New York because he couldn’t afford transportation. He would spend all day walking, in a full suit and dress shoes, from Brooklyn to Manhattan to pick up prescriptions and get out the house. Yet, he still made time for his daughters, and occasionally had bursts of energy that inspired him to paint.

When my grandfather’s depression worsened, my grandmother had to start working. The dream of marrying a lawyer had faded, and the reality of supporting the family fell on her shoulders. She bore the weight without complaint, as she had always done.

You see, Nandi has never had an easy life that went according to her expectations. She grew up thinking she had the dream 1920s Black family—her father a dentist, her mother a nurse. Both were West Indian immigrants from Barbados, instilling in her a strong sense of cultural identity and the importance of professional achievement. But that illusion shattered when her father divorced her mother and started a family with her mother’s best friend. Betrayal and abandonment were lessons she learned early.

Her sister, Aunt Laverne, whom she adored, had

rheumatic fever, and Nandi was obliged to take care of her, especially after their mother died when Nandi was just 28. Then, when she was 45, Aunt Laverne —her sister, best friend, and closest relative—died as well. The people she relied on most were taken from her, one by one.

Then she married a lawyer and thought she had finally won, but she inevitably lost that too when my grandfather’s health declined. Life kept knocking her down, but she refused to stay down.

I tell the story this way to paint the complexity of human life and the hidden reasons people may be the way they are. Life essentially tried to break my grandmother bit by bit. It threw her to the ground, beat her up, and while she was bleeding out, kicked her right in the face. Or at least, it tried. She told life, “Go to hell,” because my grandmother, at 95, is still here, pouring what she can into the people around her, even if sometimes it comes off as rash.

Nandi has her “Nandisms,” sure.

Beyond her famous moments—for instance, she doesn’t eat pork but eats a ham sandwich for some odd reason. She knows how to cook extensively and how to sew, making clothes she liked from the stores. But more than anything, the most admirable quality of Nandi is that she never complained. Despite what life threw at her, she took the punches and kept rolling with it. She never gave up. That’s a fortitude I aspire to have and hope lives in me.

My grandfather later developed Parkinson’s disease and passed away a year before I was born. Unfortunately, we have none of his paintings.

But his spirit lives on—in the poetry he recited, the grace he shared, and in his daughters.

Supposedly, he also lives in me. Apparently, we sit the same way, our temperaments match, and he had a strong desire to be curious, which I find in myself. I don’t come from a tradition that believes in reincarnation, but I like to think parts of him were reborn in me.

When I ask Nandi about all the Black professionals in her family at a time when that was so rare, she says, “West Indians believed you have to be something; you can’t be nothing.” While this mindset can be problematic, for sure, there’s something about the aspiration for greatness that lives in me from both of them.

Greatness is in my genes, and channeling that towards the good is what I seek to do in the world. From Nandi, I inherit resilience, toughness, and the ability to face harsh truths without flinching. From Grandpappy, I inherit curiosity, creativity, and a touch of grace. I owe them my drive, my love, and my complexity, and I wouldn’t trade my roots for anything in the world.